Is build-to-rent part of every Australian developer’s future?

On a recent webinar, Altus Group experts discussed the future of build-to-rent development in Australia.

Key highlights

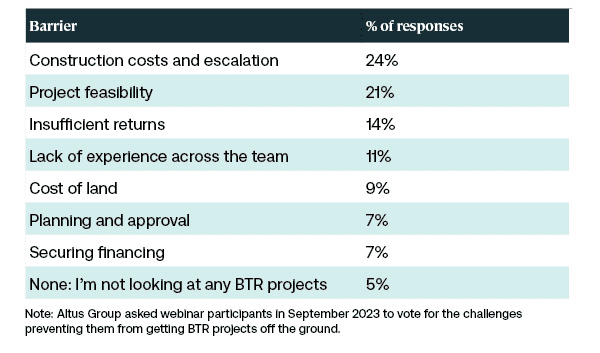

Construction costs, feasibility and insufficient returns are the three biggest barriers preventing build-to-rent projects from getting off the ground in Australia, according to an online poll conducted by Altus Group

In a webinar hosted by Altus Group in September, Niall McSweeney and Anthony Lisbona looked at the roadblocks in the way of successful BTR developments and offered a clear call to action to Australian developers

What is the future of build-to-rent in Australia?

Altus Group’s President of Cost and Project Management, Niall McSweeney, and Offer Manager Anthony Lisbona recently sat down with James Barlow, Enterprise Account Manager at Altus Group, to share their insights in The Future of Build-to-Rent in Australia.

Tight rental markets, interest rates hikes, supply shortfalls and rising net migration are all putting pressure on housing affordability at a time when institutional investors and large developers are looking beyond the traditional asset classes of office and retail. As demand drivers converge, local and international investors are making moves into the build-to-rent (BTR) sector.

Analysis by EY has found BTR currently accounts for just 0.2% of Australia’s housing stock, but with the right settings, more than 150,000 new BTR homes could come to market over the next decade. In fact, the Australian Government is looking to the nascent asset class to help it hit an ambitious target of 1.2 million new dwellings by 2029. The May 2023 Federal Budget outlined taxation changes to encourage BTR, including a 50% reduction in the withholding tax rate for managed investment trusts. State governments are also offering incentives, including land tax concessions and exemptions from foreign investor land tax surcharges.

“We see this as a very desirable asset class for the delivery partners, for the end owners and for the actual population at large,” McSweeney said. Altus Group has seen significant interest from clients, both institutional owners and private developers. But moving into BTR is not simply a matter of ‘build it and they will come’.

Breaking down the BTR barriers

Nearly a quarter of poll respondents (24%) noted construction costs and escalation as the biggest obstacle in the way of them starting a BTR project – and this comes as no surprise to Altus Group. Construction is, after all, one of the biggest input costs of any project. But for BTR, costs include not just those incurred upfront, but also during maintenance and refurbishment works.

Successful BTR requires an “operational mindset,” McSweeney noted. Developers cannot simply “rebadge” build-to-sell product. What he called “true BTR” is more akin to running a hotel or student accommodation – which “comes down to the brand” and the resident experience. “The real key is making sure you’re not cutting corners at the beginning and sacrificing the long-term… cleanliness or general maintenance.” Following construction costs, the next biggest barriers were project feasibility (21%) and insufficient returns (14%) – and Lisbona had some fascinating insights to share.

Assessing the feasibility of BTR can be broken into two parts, Lisbona said. There are the “indirect metrics” like reputation and strength of the brand, which can influence an operator’s ability to attract tenants. Service and responsiveness to maintenance requires can impact the ability to retain tenants, he noted.

Direct metrics include all the financial inputs. Because the objective is to hold over a long period, perhaps as long as two decades, there is “a different mindset,” Lisbona agreed. “There is more of a focus on yield, your exposure to interest and debt is a lot longer.” Interest coverage and debt servicing ratios are more important, as are tenant turnover costs. Owners must consider how capex and maintenance costs will impact cash flow over time.

Land acquisition costs can make or break feasibility, and the cost of land per unit is a sticking point, the pair said. In Melbourne, land costs account for around 12% of a project, McSweeney noted, in comparison to 35% in Sydney. “That really gives you an idea of why we are seeing the emergence of this product class in Victoria rather than New South Wales.”

Figure 1 - What roadblocks are preventing BTR projects?

Lisbona also points out that BTR still faces several other “big blockers” in Australia. One of the obvious ones is the inability of developers to reclaim GST on capital costs. BTR landlords cannot claim back the 10% GST incurred on third party costs associated with leasing activities, construction costs and maintenance. “Straight away that increases your capex by 10%. You have to borrow more money. You can't reclaim that back from the ATO,” Lisbona said. Access to capital is another roadblock (and 7% of respondents to Altus Group’s poll noted it was the biggest factor preventing them from moving into the BTR space).

As BTR is an emerging market in Australia “there isn't much comparable data,” Lisbona said. The National Multifamily Housing Council in the US is a treasure trove of data on demand, construction costs, finance and investment, economic impact, market conditions and more. But Australia is yet to build its arsenal of data and banks are still “hesitant” to lend “when developers don’t have any runs on the board”. As such, private developers must look further afield to alternative sources of funding, like a debt fund. “But even then, some of those debt funds will have certain sustainability targets they'll have to achieve as well. So, it’s not simple,” he added.

Technology can also be an impediment, as most off-the-shelf systems aren’t suitable to the Australian market. While some BTR operators can integrate “best of breed” technology, others are having to build technology solutions “from the ground up” – and this can come at a considerable cost.

Of those polled by Altus Group, 11% noted lack of skills as a barrier to BTR in Australia. Developers are on hunt for the best people, Lisbona said, and are having to lean on other sectors, like student accommodation or co-living. This isn’t simply a delivery problem – it also influences the ability of developers to assess opportunities at the feasibility stage. Many developers are having to outsource their analysis, “and this slows down the process”.

Planning and approvals presented the biggest barrier for 7% of those polled by Altus Group. “Layers of approvals” adds extra time to the schedule, McSweeney added. “Time is now the big thing that is really hurting feasibilities because the holding costs are too much... and that is eating away at that very narrow margin.”

Forecasting the future

Organic growth will, with time, alleviate some of the current inhibitors. Others, such as GST, are in the hands of governments. But one of the biggest accelerators will be the imperative to upgrade older commercial stock, Niall observed. Increasing pressure on valuations and vacancies is tempting some developers towards adaptive reuse. The national vacancy rate stands at 12.8% in CBD markets, and 17.3% outside CBDs – but zoom in on lower-grade stock and “we are seeing 30% or 40% vacancy” in some markets. “BTR is an obvious solution,” especially for offices in city centers, near public transport or social infrastructure.

The upside of adaptive reuse is speed to market – provided the feasibility stacks up – “because then you are looking at repositioning rather than a total knock down and rebuild”. BTR can alleviate the waiting game because there is a single entity, and the asset is “generally held in one stratum”. And with its emphasis on “repetition and standardisation”, BTR can deliver cost savings during construction, as well as more opportunities for “off-the-shelf” repair options.

What will Australia’s BTR models of the future look like?

Lisbona pointed to the Assemble Futures build-rent-buy model – “a different take on BTR” that provides an “alternative pathway to ownership”. Other developers are embracing a “hybrid strategy” with part BTS and part BTR to minimise their exposure to risk.

In Germany and Scandinavian countries, renters of BTR apartments choose an “empty shell” that they fit out to suit their own needs – down to the flatpack kitchen. That may be a bridge too far for Australia’s market, McSweeney noted. Perhaps the UK model, where adjoining units can be connected and reconfigured as residents’ needs change, will be more palatable to Australians. “It's a bit like the dual key scenario you see in some serviced apartments.”

When thinking about BTR, many complex and competing challenges come into play. But Altus Group’s experts offered a clear message to the webinar audience: Don’t think about what is happening now. “Rental vacancy rates, levels of supply or competition in the market today are meaningless,” Lisbona said. What will the vacancy rates look like in a decade’s time? What supply is coming online? How will the infrastructure in the area evolve over time? These are the questions that can help Australian developers determine whether build-to-rent is part of their future.

Authors

Niall McSweeney

Head of Development Advisory, Asia-Pacific

Anthony Lisbona

Product Manager

Authors

Niall McSweeney

Head of Development Advisory, Asia-Pacific

Anthony Lisbona

Product Manager

Resources

Latest insights

Jan 9, 2025

Building the future - Key trends shaping Australia’s construction industry in 2025